Thank you! Your submission has been received!

Oops! Something went wrong while submitting the form. Please try again.

In July and August I will be travelling to Kabwe, Zambia for my first stint of fieldwork. I will conduct research into the multispecies environmental history of the mining town which during the colonial period was known as Broken Hill. Whilst there I intend to visit archives in Lusaka, Ndola and Livingstone, which will be combined with getting to know the town and its environs. In anticipation of my journey I wanted to use this blog post to share a snapshot of the insights from my research into the more-than-human history of Broken Hill. My research is framed around categories pertaining to the features of Kabwe’s biosphere so as to present as full as possible a picture of the environmental history of the lead and zinc mining town. These categories are: geology and geography, water and wood, food and fodder, muscles and miners and finally wealth and waste. For this blog post I will share some of my findings concerning the categories geology and geography as well as food and fodder. More specifically, I will provide tentative answers to two questions: How was industrial mining influenced by the geology and geography of the Broken Hill area? And how were animals incorporated into the emerging economy then centring on the lead and zinc mine? In answering this latter question I will share some of the issues that I have thus far encountered researching the history of animals at Broken Hill. Namely, that historians have taken for granted that the prevalence of tsetse fly in Northern Rhodesia prevented the use of animals such as cattle, donkeys and horses. I then conclude this blog post by posing further questions that should guide my research into the history of cattle in Broken Hill.

As an economic activity mining is uniquely bound to the geography in which it takes place. This is because an area’s geology determines whether or not there are minerals and metals that are worth extracting. If these conditions are not met then financiers and miners would not undertake the risk of sinking their money into a mining venture. It is because of this risk that capitalists in the colonial period relied heavily on the exploration and prospecting work of geologists to determine sites of worthwhile investment and extraction.[2] At the dawn of the twentieth century when disciplinary and professional boundaries were less clear cut, those with personal experience in the mining industry could also be relied on to identify ore deposits.[3] This was the case when the Rhodesia Copper Company hired the Australian mining engineer Thomas Davey to prospect for copper deposits in the centre of the territory that would become known as Northern Rhodesia following the establishment of British South Africa Company (BSAC) rule.[4] The life and career of Davey before his arrival in southern Africa remains something of a mystery but that he had at least seen the lead-zinc mine at Broken Hill in New South Wales, Australia is generally accepted by historians.[5] The fact that an Australian was working inside the BSAC’s territory is testament to the British imperial world that had been forged by the 1900s.[6] The southern African mining industry was drawing in expertise from across the imperial sphere as well as from continental Europe and North America and Davey was no exception.[7] Following in the footsteps of geologists such as René Jules Cornet, who conducted the first systematic geological survey of Katanga in 1891-93, and Franz Edward Studt who had been the geologist on George Grey’s second expedition to Katanga in 1901, Davey had set out in early 1902 to explore for pre-colonial copper workings in the area that would become the central province of Northern Rhodesia.[8] It was in this expanse of savannah grassland and Miombo woodland that he came to discover the site of the lead and zinc mine of Broken Hill.

Davey, accompanied by African guides, porters and an assistant by the name of A.C.M. Kerr, were in the area of the future mine at the height of the rainy season. In his December 1902 account of the discovery Davey reported that “on my arrival in the vicinity of these old workings my guide explained to me through my interpreter that he had mistaken his bearings…. It was raining heavily and getting rather late in the afternoon, and I therefore decided to camp for the night.”[10] Having established camp Davey and an African guide began wandering across the veld and “saw in the distance what appeared to be a brown ironstone kopje.”[11] Photographs taken following the commencement of mining operations in 1904 reveal a tall 50 foot high hillock with two peaks joined by a shallow saddle which excavations revealed to have been internal subsidence of the rock formation.[12] His interest piqued, Davey made his way to the hill reporting that on “reaching the kopje I commenced to nap the stone as I ascended. At first… I discovered a little limestone as well as hematite, but it was not long before I broke a heavy piece of stone which was perfectly white, and which I at once recognized as cerussite or carbonate of lead.”[13] Further exploration revealed to Davey “sulphides of lead as well as carbonates of zinc.”[14] For the next 5 days, Davey and his assistants pegged out claims on the kopje and recognized that “there were other kopjes of rather similar dimensions also consisting of lead and zinc ores.”[15] What the Australian had stumbled upon were several lead-zinc orebodies which jutted out from the surface in the form of these striking hills which in turn bore resemblance to the lead and zinc deposits discovered at Broken Hill, Australia some decades before.

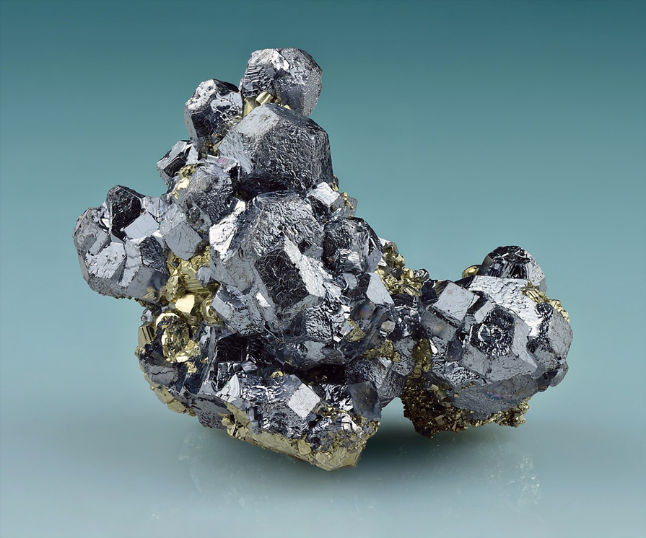

These outcrops consisted of oxidised ore of lead and zinc known as cerussite and hemimorphite respectively. These rocks were weathered materials from the main pipelike orebody that descended through the earth’s crust below the hill. This mineral deposit was encased in a massive dolomite formation which was formed by the deposition of layer upon layer of rock 880 to 765 million years ago.[18] The orebody is about 680 million years old, give or take 13 million years. The orebody is polymetallic, mineralogically complex and consists predominantly of sphalerite (the natural mineral of lead sulphide) and galena (the natural mineral of zinc sulphide).[19] It is from these two minerals that lead and zinc are processed into their final products as tradable commodities. The extracted ore was crushed into smaller particles of rock which were then sent into massive furnaces where they would be roasted and broken down into lead sulphide concentrate and zinc sulphide concentrate respectively.[20] These concentrates would then be treated and cooled forming lead and zinc ingots and transported by wagon and then by train to the ports of Beira, Port Elizabeth and Cape Town.[21] As a result of its mineral abundance the area of Broken Hill became integrated into the wider regional economy that was then being formed on the back of the growth of British, South African, German and Belgian financed mining.

The demand for these metals in the industrial economies of southern Africa, Europe and North America was due to their utility. The lead extracted from Broken Hill would have been used for paint, protective coatings, ammunition, burial vault liners, as well as to cover electrical and telephone cables. Furthermore, lead was also used for metal alloys such as solder which was used to connect metal joints.[22] Zinc historically was used for metal galvanisation, where zinc was applied as a protective coating to other metals to protect them from the effects of oxidisation, and along with metals such as copper to produce alloys.[23] Recognising the use and value of these materials for the global economy, financiers such as Edmund Davis leapt upon the discovery and sought to bring mining operations at Broken Hill to fruition. Having been granted concessionary rights by the BSAC, Davis and other affiliates listed the Rhodesia Broken Hill Development Company (RBHD) on the London Stock Exchange in November 1904 with operations on the No.1 Kopje (as the hillock that Davey claimed would become known as) beginning shortly thereafter.[24] The history of mining at Broken Hill can then be said to have begun with the excavation of the kopje with the subsequent growth of a sprawling settlement and the transformation of the natural environment all being traced back to the initial discovery of the mineral deposit.

The influence of geology and geography on industrial mining is quite clear. Were it not for the presence of oxidized lead and zinc on the surface of the No.1 Kopje in all likelihood industrial mining operations at Broken Hill would not have commenced. From 1904 the mine at Broken Hill (later Kabwe from 1964) would be responsible for the production of lead and zinc, the growth of an urban settlement that would become the town of Broken Hill (later Kabwe) and the radical transformation of the landscape to the site that it is today. The importance of a location’s geology and geography for the development of a mining operation cannot be overstated. In the coming months, I hope to build off these insights and delve into greater detail about how the geology and geography of the site came to influence mining operations and the related growth of the town. Furthermore, I want to understand how the area itself was transformed by mining. Hints of these changes are alluded to in my own research thus far, the digging out of No.1 Kopje to form a vast open pit, the mass vegetation clearance of the Miombo woodland in the surrounding area and the imposition of settler agricultural practices in the district as a consequence of the growth of the settlement and the arrival of the railway. A further transformation would have been the introduction of cattle for sale and slaughter so as to feed the thousands of hungry workers who had flocked to the mine from across the subcontinent. These creatures, mostly silent in the existing historiography of Kabwe, are what I turn to next.

Until now there has been little historical research into the experiences of cattle at Broken Hill, let alone an understanding of how the animals were integrated into the mining operations and growing settlement.[26] This is not simply a matter of anthropocentrism but is also a consequence of scholars noting that the prevalence of tsetse fly in Northern Rhodesia meant that animals such as cattle could not live and work in large parts of the colony. This was due to the lethality posed by tsetse fly (variations of the species Glossina morsitans), who are the vectors of the parasites Trypanosoma Congolense and Trypanosoma Vivax, otherwise known as “nagana” which can infect both humans and livestock.[27] When the fly bites into the skin of an animal it transfers the parasite directly into the animal’s bloodstream. The parasite then multiplies in the blood of the host animal often resulting in death should they not be immune to the disease. The former colonial official John Ford in his study on trypanosomiases in Africa provides a vivid account of a study where an ox in Southern Rhodesia was purposefully injected with the parasite in 1952. The researchers saw that the animal developed a fever and that his “weight fell from 584 to 462 lb during the first sixteen weeks” of infection. Following this the ox’s “general condition deteriorated… he became lazy and dejected with drooping extremities and staring coat. He became weaker until he could not keep pace with the herd.” The ox’s suffering also included his hair falling out and a debilitating loss of appetite. Were it not for the interjections of the researchers who used cotton seeds and a mineral supplement in the ox’s hay ration, then the creature would most likely have died.[28]

The lethal potential of tsetse fly prevented the use of cattle and horses in large parts of Northern Rhodesia. This has meant that historians have taken for granted that livestock and draught animals played little to no role in the development of Broken Hill as a mine and settlement. This has meant that there have been few attempts to find animal traces in archival records concerning the mine and town. This led me to think that researching and writing about the role of cattle at Broken Hill was a dead end. This was until I stumbled upon the work of Léa Lacan whose recent study illustrates how the colonial state attempted to manage the tsetse fly problem through interventions such as the shooting of wildlife and vegetation clearances.[29] As a result of these efforts large tracts of Northern Rhodesia became tsetse free. My presumption is that this may have been the case with Broken Hill as the growth of the mine and town meant that the surrounding vegetation was cleared which could have been responsible for the eradication of tsetse fly in the area. If and how this was done will be an important component of my own multi-species history as this is a prime example of how the environment was altered by mining. Furthermore, it will serve as a fantastic means of connecting to the history of cattle at Broken Hill as further reading did yield traces of their presence at the lead and zinc mine, a presence that my own archival research and fieldwork will shed further light on.

Evidence of cattle at Broken Hill appears in some social and economic histories of trade and agriculture in colonial Northern Rhodesia. Hugh Macmillan in his history of the Susman Brothers and Wulfson trading business notes that Elie and Harry Susman engaged in the cattle trade in Barotseland which lay to the west of Broken Hill.[31] The Lozi were keen cattle traders challenging the notion that the territory of Northern Rhodesia was ipso-facto cattle free, with the Lozi and the Tonga people to the East also engaging in cattle rearing and trade long before the colonial period.[32] As the historian Maud Muntemba notes in the pre-colonial period, the Lenje who occupied the region between modern day Lusaka and Kabwe kept cattle who “seem to have been used for trading, for consumption, and for conspicuous wealth.”[33] Cattle were obtained from the Tonga, along with ivory and salt for iron ore.[34] It is also likely that the Lenje engaged in the cattle trade with the Lozi kingdom to the West. Cattle then were participants in pre-colonial trade networks. Yet as Macmillan’s study goes on to reveal the Susman brothers were selling cattle at market in Broken Hill as early as 1909.[35] These cattle were being sold for the purpose of slaughter to provide a ready supply of beef to the mine’s workers and the town’s populace. It appears that cattle were integrated as participants in the economy of Broken Hill to serve as food.

The advent of colonial rule and the development of the lead and zinc mine at Broken Hill radically transformed the economy and environment of the area. With the development of the mine, there came an influx of workers, managers and company officials. Cattle were slaughtered as food for these people who were in the process of turning the scattered tents of the early mine into a bustling town. What is unclear however are the details of these cattle’s experiences at Broken Hill. Little is known about the types of cattle that were imported to, kept, fed, bred, and traded at Broken Hill. We know little about their origins, how they were treated by the European cattle traders and how African communities such as the Lenje responded to the growth of this urban market. At this preliminary stage of my research I have formulated a series of questions that I hope to answer over the coming period. Questions such as: what kind of cattle were kept, traded and slaughtered at Broken Hill? How were they fed and cared for whilst they were forced to wait for their inevitable slaughter? How did their behaviour change upon arrival in a new environment? And how did these animals interact with the physical landscape around them? Furthermore, what other roles did cattle perform at Broken Hill? Did they contribute to the day to day operations of the mine as draught power? How did the introduction of cattle impact upon agricultural practices in the area? In answering these questions I will centre the historical experiences of these animals as crucial actors in the growth of Broken Hill.

These snapshots of my research into the multispecies history of Kabwe (Broken Hill) illustrate details of the mine and town’s history that have largely been neglected by historians. The kopje that first caught Davey’s attention in 1902 led to the discovery of a deposit of lead and zinc that would go on to be extracted by a capital intensive mining operation. Responding to the global demand for lead and zinc as useful commodities, financiers such as Edmund Davis formed the Rhodesian Broken Hill Development Company to extract and then sell the minerals and metals of the now christened Broken Hill Mine. As workers flocked to seek wage employment at the mine a town developed that would over time draw in people from across southern Africa and the wider British imperial world. The geography of the landscape would change as the kopje was dug out, trees were cut down for firewood and building materials, and settler farms established along the line of rail that would connect Broken Hill to the ports and cities of southern Africa. As I conduct archival research and fieldwork in Zambia I hope to illustrate and analyse these environmental transformations and integrate them with an account of how other elements of the biosphere such as animals came to shape and were shaped by industrial mining.

A hitherto neglected aspect of Kabwe’s history has been the experience of animals such as cattle. As I have outlined historians have taken for granted that the prevalence of tsetse fly prevented their use in large parts of Northern Rhodesia. Further digging demonstrated to me that tsetse fly are in of themselves worthwhile subjects of historical inquiry in that they were and remain crucial components of the natural environment. Furthermore, a potential feature of the environmental story of Broken Hill is that mass vegetation clearances and game shooting could take place as a result of the development of the town which in turn would have affected tsetse fly. I am certainly interested in learning more about this and I hope that it will be a part of my final dissertation. In addition to grappling with tsetse fly I have also illustrated the potential for cattle-centred history at Broken Hill as I have found scattered references to their use as a food source for the burgeoning settlement. There is still much to be done as I believe that in integrating their stories we can come to a greater understanding of how mining transformed the biosphere of the area. It is with this in mind that I eagerly await my first journey to Zambia.